Transliteracy as a concept originated in the work of academics who were involved in digital building and tinkering, people who got their hands dirty with some practical work while thinking theoretically (see Transliteracies Project and Transliteracy Research Group Archive). And that is the essence of transliteracy – it is an abstract idea, but also an embodied practice and sensory experience. Transliteracy is neither an idea nor a practice: it is both. It is hardly surprising that librarians at the coalface of information and digital work embraced the concept as they recognised it in their everyday work with information, knowledge and technology.

But what is it exactly? A short answer is that transliteracy is about a fluidity of movement across a range of technologies, media and contexts.

A longer answer is more layered as it is based on a careful analysis of research data:

Transliteracy is an ability to use diverse analogue and digital technologies, techniques, modes and protocols

• to search for and work with a variety of resources

• to collaborate and participate in social networks

• to communicate meanings and new knowledge by using different tones, genres, modalities and media.

Transliteracy consists of skills, knowledge, thinking and acting, which enable a fluid ‘movement across’ in a way that is defined by situational, social, cultural and technological contexts.

A study into transliteracy on which this definition is based provides plentiful examples of transliterate behaviours. A historian presents research data on a website for community use, responds to online queries about family connections, puts people from the community in touch with each other and notes their experience for research purposes. An academic studies parks as public spaces and uses GPS, digital and hard-copy maps, hand drawings made by park visitors, audio-recordings and then publishes reports, brochures, academic journal articles and a website with multimedia. A teenager explores a known fictional text by taking a perspective of an inanimate object or a minor character and expresses her creative reading in a digital story. High school students and scholars alike use resources in analogue and digital forms, create new content, and collaborate and communicate in a variety of modes.

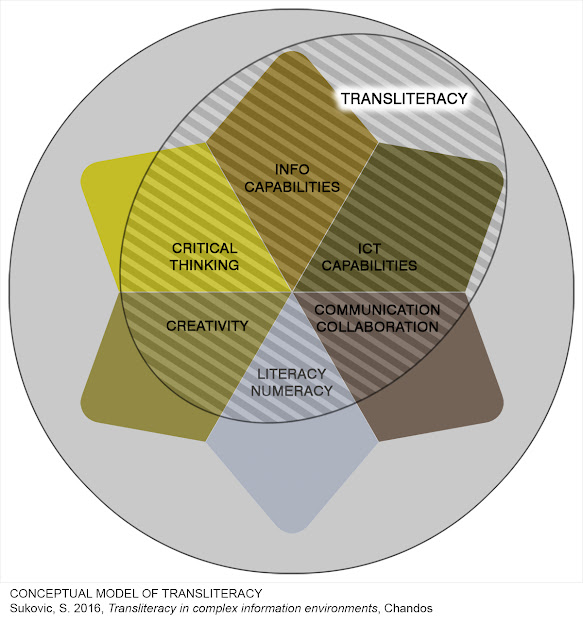

As any educator would have noticed, there are a number of skill sets and capabilities packed in the definition and examples. We can represent transliteracy conceptually with different capabilities as its main components.

Transliteracy comes to the fore in information and technology rich environments, so it is based on information and ICT capabilities. It also encompasses creativity, critical thinking, and communication and collaboration. These are the main skill and knowledge components of transliteracy. These defining components are not situated wholly in the transliteracy framework as they can be observed regardless of transliteracy. Literacy and numeracy underpin transliteracy in the same way they enable any learning.

In order to understand and appreciate transliteracy, it is helpful to understand ‘ICT’ as a label for analogue and digital information and communication technologies, and their many combinations. ‘ICT’ often refers to digital technologies. However, the book, and traditional radio and television are also technologies designed to carry information and facilitate communication. As the line between different types of technologies becomes increasingly blurry, familiar technologies become a thing of the past and old technologies undergo a revival, any technology that helps us to transmit information and communicate is relevant to transliteracy.

Transliteracy existed well before digital technologies, but contemporary ways of interacting with information and digital tools sped up, broadened and changed our daily ‘movement across’ information and technological fields. As technologies, skills and contexts in which we live and work are constantly changing, transliteracy becomes a literacy of the modern era. It is integrative in a sense that it doesn’t want to replace other useful ways of thinking about information and technology. Rather, it provides an integrative framework for bringing together modern literacies (e.g. information, digital, media literacy). It also provides a framework for connecting rational-emotional, analytical-creative and theoretical-practical ways of thinking and working, which enable us to live effectively and creatively with abundant information around us.

The next post in this series will introduce transliteracy palettes and consider the development of transliteracy in formal and informal learning environments.

See Part 1: Transliteracy: the art and craft of ‘moving across’ – LARK blog and SciTech Connect

Transliteracy in Complex Information Environments is scheduled to publish in November. If you would like to pre-order a copy, please visit the Elsevier Store. Apply discount code STC215 at checkout for 30% off the list price and free global shipping.

0 Comments