By Suzana Sukovic

Last night on Q&A Brian Cox said exactly what librarians have been saying for years, but it echoes much better coming from him. Tony Jones started by quoting Cox: “Changing your mind in the face of evidence is absolutely essential to the civilised democratic society” and continued, “The questioner is asking, ‘Who should we listen to?’”

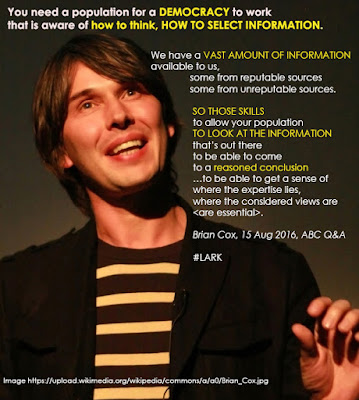

Cox’s full response could be found here (section starts at 41:58), and (again) this is the gist of his answer:

What do we need for democracies to work?

…An education system that functions extremely well. You need a population for a democracy to work that is aware of how to think, how to select information. We have a vast amount of information available to us, some from reputable sources, some from unreputable sources. So those skills to allow your population to look at the information that’s out there to be able to come to a reasoned conclusion…to be able to get a sense of where the expertise lies, where the considered views are.

Share this quote, dear library and information people. Make it visible! It is important. Nothing less than the future of democracy is at stake.

The Census has been a good reminder recently.

#CENSUS2016

Twitter has covered #Census2016 and #CensusFail thoroughly. After so much that has been said, right now I am more interested in what we as citizens and individuals need to know to make decisions and contribute to current conversations in an informed way. So, here is my non-exhaustive list of issues:

• Participation in Census: What is it? How should we complete the Census? Should we do it online or use a paper form?

• Privacy: What are my entitlements and duties? Should I protect my privacy? How? How do different technologies and government processes affect my privacy? What are the legal and personal implications of my decisions?

• Use of technology: How do computer security and hacking work? How is data linked?

• Social media: Should I participate in online discussions? Why? How?

• Society: Why do groups of people decide to hack? How is this Census affecting our knowledge about who we are as the society?

And the list goes on…

In understanding these issues and making decisions, it is crucial to be able to think critically. A good understanding of and skills to deal with information, technology, and issues of citizenship is necessary to make decisions that may have far-reaching consequences.

NAPLAN

Similarly to the Census, NAPLAN discussions can be a big ask for someone who skim reads the paper. Explanations of why Australian students are not advancing as we would like range from funding issues and selection of students for teaching courses all the way to the influence of technology or diverse ethnicities of the Australian population (see also an old but still relevant post about international test results). Whatever factors may be at play, it is sure that numeracy and literacy are quite complex and teachers are certainly not the only people responsible for their development. Last week, for example, we heard about research, which points towards a positive link between playing computer games and academic results, including science, math and reading. Alberto Posso, from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, reportedly said,

When you play online games you’re solving puzzles to move to the next level and that involves using some of the general knowledge and skills in maths, reading and science that you’ve been taught during the day (see Guardian article).

Gaming is not an isolated example of a possible influence on test results. Some of the reasons for achievements in mathematics may be that the student is an avid reader who enjoys classics or a keen musician. Research shows that both music and reading, especially of complex fictional texts, have significant influence on improving cognitive abilities. The most important questions about NAPLAN results, in my mind, concern the complexity of learning and development rather than the narrow focus on Math and English classes.

QUITE FRANKLY, WE NEED MORE INFORMATION PROFESSIONALS (and, no, I am not biased)

Transliteracy is all over these news stories with significant implications for education. Transliteracy is a framework that combines information and ICT capabilities with citizenship, creativity and critical thinking to prepare our students for a life in a fast-changing and information-rich society. It develops students’ capacity to apply their knowledge and skills in different situations, by using digital and analogue media and technologies, and to communicate with different audiences. And who is in a better position to work with information across the board than your knowledgeable and friendly librarian?

ALIA has recently pointed towards studies showing that we need more school librarians. Developing transliteracy at school means supporting students’ ability to think critically and creatively in life situations and jobs we don’t know today. A transliterate student needs to develop their numeracy and literacy in many different ways across all their subjects. S/he will be able to decide how to contribute to any future Census, to assess government decisions, and participate in public and private conversations about societal issue in an informed way. None of their teachers knows the issues she will face and cannot teach her answers she will learn by heart. S/he will, however, gain the skills to be an independent learner and thinker because school librarians will know how to work with teachers to develop essential skills in a systematic way.

Learning doesn’t finish when we get school diploma or a professional qualification. Library and information professionals in various settings are best life-long learning guides. We need more of them.

As Cox said, “Changing your mind in the face of evidence is absolutely essential to the civilised democratic society”. We need to serve the quote regularly with a good dose of fresh evidence.

Parts of this article were previously published in the Bulletin of St’Vincent’s College, Potts Point where Suzana works as Head of the Learning Resource Centre.

0 Comments