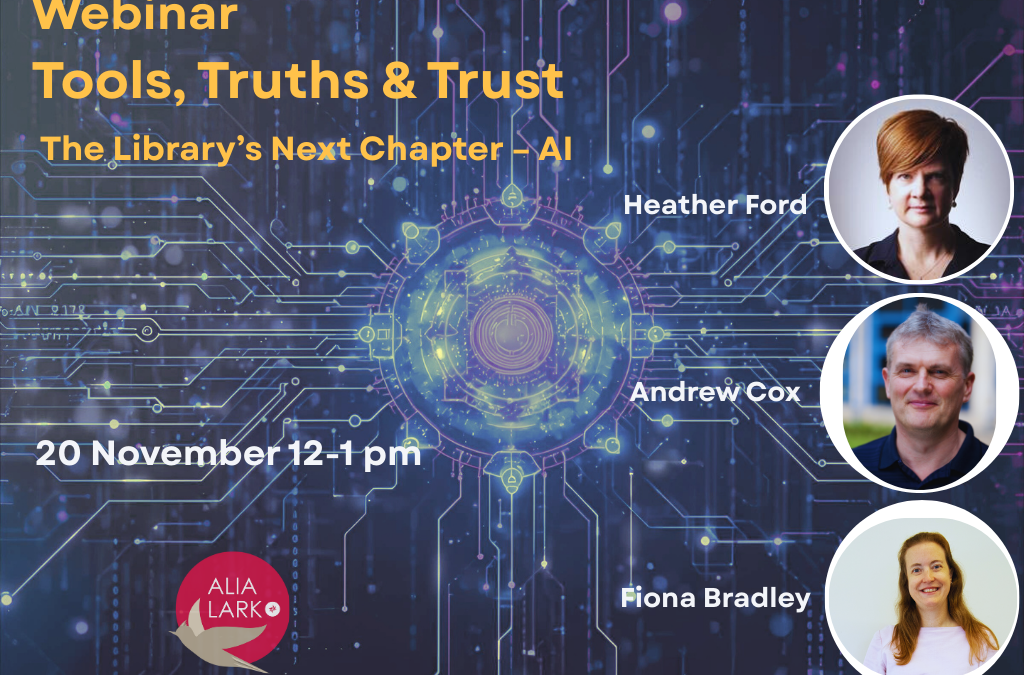

Tools, Truths and Trust: The Library’s Next Chapter – AI, the webinar held on 20 November, was LARK’s best-attended webinar in some time. Nearly 250 people registered and close to 120 attended on the day, with representation from all library sectors. The strong turnout reflected both the relevance of the topic and the calibre of our guest speakers: Andrew Cox, Senior Lecturer at the University of Sheffield in UK; Fiona Bradley, Director, Research & Infrastructure at the University of NSW; and Heather Ford, Professor in the School of Communication at the University of Technology Sydney. I facilitated the session with Paul Jewell’s timely help. A recording is available HERE (updated 21 December 2025).

Our guest speakers approached the topic of GenAI in libraries from the perspective of research evidence and its relevance to library practice. The webinar started with Andrew’s overview of key issues, followed by Fiona’s discussion about scholarly communications, and Heather’s consideration of AI literacy.

Andrew Cox: Opportunities and Challenges Posed by AI

Andrew outlined current uses of AI in libraries, noting that AI literacy initiatives and the use of AI for everyday information tasks are among the most common activities. The spread of tools such as ChatGPT and Google Overviews is changing information-seeking behaviour, with some early signs that users may rely less on traditional library resources when AI tools act as proxy search engines. Andrew highlighted both the benefits and limitations of generative AI:

- Benefits: It allows for natural language conversation, provides immediate answers rather than resource lists, and offers functionality like summarisation and translation. It can also be beneficial for learning, especially for students with disabilities and international students.

- Problems: AI is an unreliable source, producing errors, lacking citations, and showing bias and a lack of cultural and linguistic diversity. For learning, it may reduce engagement and critical thinking by offloading tasks that develop critical thinking.

The focus on AI literacy is logical because it aligns with the library profession’s identity as educators, is less resource-intensive, and is driven by user need. However, Andrew Cox noted a potential future risk: the timing of library system suppliers integrating AI functionality might tempt institutions experiencing financial pressures to use it to fundamentally change (and potentially downsize) librarian roles.

Fiona Bradley: AI and Scholarly Communications

Fiona Bradley focused on the impact of AI on scholarly communication, particularly academic publishing and discovery of published work. A core concern is who controls access to knowledge and how to maintain trust in the processes of scholarship, publishing, and open infrastructure.

Key AI-related challenges include:

- Bots and scraping: Automated scraping of repositories increases maintenance costs and causes outages, which require technical solutions and cross-sector collaboration.

- Provenance: Large language model chatbots make it harder to trace ideas back to their original sources. Persistent identifiers and robust metadata practices are essential for preserving accuracy and context.

- Flattening of debate: Chatbots can obscure disagreement or nuance within a field. Many AI-powered discovery tools also struggle with the interpretive depth of the humanities and social sciences, partly because older scholarship is central to these fields, but often undigitised.

Fiona encouraged librarians to engage users in these issues through workshops, training, and updated guidance that draws on established information literacy expertise.

Heather Ford: AI Literacy

Heather Ford emphasised the potential of librarians to lead the public push for AI literacy. While national AI strategies tend to frame AI literacy in economic or workforce terms, libraries are often overlooked despite their long-standing commitments to equitable access, critical engagement with information, and public learning.

The library sector argues its suitability for leading AI literacy because libraries are

- Trusted institutions with core commitments to access and equity

- Professionally skilled in navigating complex information systems

- Capable of addressing both the opportunities and harms of technology.

Heather Ford emphasised the role libraries can play in strengthening public AI literacy. Library research frames AI literacy as broad and evolving, encompassing ethical and critical dimensions as well as technical, policy and interpersonal skills. It builds on existing digital and data literacies and focuses on understanding underlying mechanisms, evaluating claims, and considering societal implications. Heather concluded that libraries are well placed to shape AI literacy as a democratic practice, not merely a workplace competency.

Discussion: Knowledge and Librarians’ Roles

The participants discussed the possibility that humanisation of AI may lead to reshaping ideas about knowledge and thinking. The general consensus was that knowledge remains a distinctly human practice and that technologies are tools to facilitate knowledge processes. Andrew Cox stated the profession’s fundamental driver is to enable equitable access to reliable knowledge, which AI subverts with inaccurate information.

The panel discussed the changing role of librarians and their relationship with users. Librarians act as crucial, often hidden, cultural intermediaries in enabling knowledge, critical thinking, and community, Heather Ford stressed. Fiona Bradley mentioned that examples from her library practice, such as hosting workshops and discussions on AI, and enhancing systems to ensure robustness and trust in scholarly communication.

The biggest promise and opportunity, according to the speakers, is the agency and choice to influence narratives and systems, ensuring that AI serves people, particularly minoritised groups, and is linked to principles like democratic flourishing and national sovereignty.